At the Origins of Valve Replacement: When the Idea Seemed Impossible

This account reminds us of a fundamental truth: the remarkable advances of modern cardiology are built on decades of experimentation, setbacks, courage, and humility.

Every valve implanted today is the direct heir to those early steps—sometimes tragic, but profoundly human.

A Time Marked by Very Real Limits

For decades, valvular heart disease slowly condemned those who suffered from it.

Heart murmurs were heard, symptoms were recognized, and some valves could already be addressed through commissurotomy procedures. But the idea of replacing a heart valve remained beyond reach.

The Meeting of Two Visionaries

In the late 1950s, two paths that seemed worlds apart were destined to cross. One came from surgery, the other from engineering. Together—without fully realizing it—they would open the door to a new era.

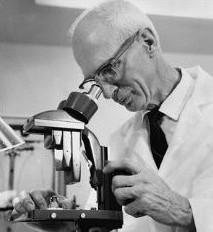

At the age of 63, Albert Starr founded the cardiac surgery program at the University of Oregon. His ambition was clear: to build a service capable of rivaling that of Dr. Walt Lillehei in Minnesota, then considered a world reference.

Shortly after his arrival, a man came to see him—not as a patient, but with a bold idea. Lowell Edwards, a hydraulic engineer, dreamed of building a mechanical heart.

The concept was intriguing, but Starr proposed a more realistic compromise: to begin by replacing a heart valve.

This choice, seemingly modest, would change the history of cardiology.

Before moving forward, three fundamental questions had to be answered:

- how to simplify the complex mechanics of the mitral valve;

- which material could withstand millions of openings and closures;

- how to securely anchor an artificial valve within a heart in constant motion.

First Steps: Learning from Failure

The pioneers moved forward without a map. Each success was fragile; each mistake carried serious consequences.

The first prototype consisted of a ring topped with two semi-circular metal leaflets, held in place by a central bar that allowed unidirectional motion. Animal experiments were encouraging: the dogs survived the surgery, and cardiac function appeared satisfactory.

But the days that followed revealed a harsh reality. All developed fatal pulmonary edema. Autopsies identified two major problems: imperfect fixation of the valve and the formation of fine bloodBlood is composed of red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, and plasma. Red blood cells are responsible for transporting oxygen and carbon dioxide. White blood cells make up our immune defense system. Platelets contribute to blood clots on the metal leaflets, ready to detach.

The conclusion was unmistakable: this model could not work in humans. Failure thus became a source of learning.

The Decisive Idea

Perseverance sometimes opens an unexpected door.

A second prototype is developed: a mobile ball enclosed within a cage, attached to a ring sewn to the cardiac skeleton. The hope is that the constant motion of the ball will prevent clot formation.

The improvement is real, but incomplete. BloodBlood is composed of red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, and plasma. Red blood cells are responsible for transporting oxygen and carbon dioxide. White blood cells make up our immune defense system. Platelets contribute to blood clots still form on the sewing ring, potentially blocking the ball and causing sudden valve failure.

Nevertheless, in the spring of 1959, Lowell Edwards introduces a decisive technical improvement. In animal studies, the long-term success rate reaches 80%. The moment to take the next critical step is approaching.

The Transition to Human Surgery: Courage, Hope, and Tragedy

At this stage, the boundary between experimentation and hope becomes fragile.

In the summer of 1960, the head of cardiology in Oregon, Herbert Griswold, urges the team to move forward. Patients with end-stage severe mitral valve disease, with no other therapeutic options, are waiting for a solution.

Norma Forbes becomes the first patient to undergo mitral valve replacement. The operation itself proceeds without major incident. All parameters are reassuring. Then a simple, ordinary moment occurs: tired of lying on her back, she asks to be turned onto her right side. Dr. Starr assists her in repositioning, and at that very moment, she suddenly dies in his arms.

The autopsy reveals the cause: a massive air embolism. Not all the air had been removed from the heart after the valve replacement procedure.

A dramatic technical error, similar to those experienced by other pioneers, including Drs. Charles Bailey and Lillehei.

The Beginning of a New Era

The history of medical progress is often written through second attempts.

Starr’s second patient, a 52-year-old man, becomes the first survivor of a research program lasting only two years and dedicated to the development of an artificial heart valve.

It is at this precise moment that the era of valve replacement truly begins.

One year later, the first artificial aortic valveThe aortic valve is located between the left ventricule and the aorta. It is one of the four valves ot the heart. >> is successfully implanted.

Safety, Durability, and Legacy

Over time, individual boldness gives way to collective science.

In California, Edwards Laboratories demonstrate that these ball-and-cage valves can function for more than 40 years, at a rate of 60 beats per minute, without mechanical failure.

Clinical outcomes improve rapidly. Operative mortality, which approached 50% during the first year of Starr’s program, steadily declines. Today, it is close to 3%, and even as low as 1% in patients who are otherwise in good health.

Even at that time, the pioneers understood a fundamental principle: operative risk must always be interpreted in light of the severity of the underlying valvular disease and the patient’s overall condition.