Episode 14 – The Invention of the Pacemaker

- Home

- »

- History of cardiology

- »

- Episode 14 – The Invention of the Pacemaker

At the time when cardiac surgery was beginning to develop in children with congenital heart defects—such as a hole between the two ventricles—sudden death caused by an electrical conduction disorder of the heart was a dramatic complication.

Even when the heart muscle itself was intact, a complete electrical block could abruptly stop cardiac activity.

Albert Hyman: an idea ahead of its time

As early as 1932, well before cardiac surgery was truly practiced, a physiologist named Albert Hyman proposed the idea of an artificial pacemaker.

His device worked in animals. Was it ever used in humans? He never clearly stated this.

In any case, this idea—far ahead of its time—remained largely ignored for many years.

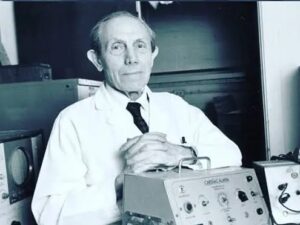

Paul Zoll: a clinical shock

A graduate of Harvard Medical School, Dr Paul Zoll became interested in the artificial pacemaker following the striking death of one of his patients.

This 60-year-old woman suffered from repeated episodes of loss of consciousness, associated with an extremely low heart rate of around 30 beats per minute.

The electrocardiogram revealed a complete heart conduction block: the electrical impulse was no longer able to travel from the atriaThe atria are the two upper chambers of the heart. They act as reservoirs for blood that will fill the ventricles. to the ventricles.

A defining moment

The death of this patient—whose heart was otherwise structurally normal—was a profound shock for Dr Zoll.

For him, this death was not inevitable; it called for a solution.

A wartime image as a starting point

A deeply buried memory then resurfaced: the image of a wounded soldier during the Second World War.

Dr Zoll recalled a key anatomical detail: the esophagus, the tube connecting the mouth to the stomach, passes directly behind the heart.

Image, imagination, intuition

In an anesthetized dog, he inserted an electrode mounted on a metal rod into the esophagus.

The result: he was able to electrically stimulate the heart.

The experiment worked—but the device was impractical for clinical use. Another approach was needed.

A second inspiration

While observing a dog’s chest, Dr Zoll noticed its triangular shape. The idea then emerged to place two electrodes directly on the skin, on either side of the chest.

This method worked.

The first attempt in humans

The first human application was performed on an 82-year-old man, a neighbor of Dr Zoll’s father, who suffered from repeated fainting episodes.

Once again, the diagnosis was confirmed using an electrocardiogram.

The electrodes were positioned on the chest, on both sides of the thorax.

According to Dr Zoll, this attempt had three possible outcomes:

- no effect,

- effective electrical stimulation of the heart,

- or electrocution of the patient.

Electrical stimulation was achieved and maintained for 40 minutes, stopping the episodes of loss of consciousness.

The patient later died, likely as a result of multiple intracardiac injections received prior to this electrical stimulation.

Three fundamental demonstrations

Despite its limitations, this experience demonstrated three essential principles:

- electrical stimulation can trigger a cardiac contraction;

- stimulation can be delivered through the skin, without direct contact with the heart;

- the human heart rhythm can be controlled by a machine.

A major breakthrough… but still imperfect

This external pacemaker remained rudimentary. It required bed rest, limited movement, and could only be used temporarily.

Nevertheless, it marked a decisive step, paving the way for the development of implantable pacemakers, which would permanently transform the management of heart rhythm disorders.

Walt Lillehei: the surgeon facing heart block

In Minneapolis, Minnesota, the surgeon Walt Lillehei is confronted with a major problem: cardiac electrical conduction block occurring during certain heart surgeries.

Heart block during surgery

Repairing a hole between the two ventricles—a congenital heart defect—requires closing this opening with sutures.

However, this area lies very close to the electrical pathways that allow impulses to travel between the atriaThe atria are the two upper chambers of the heart. They act as reservoirs for blood that will fill the ventricles. and the ventricles.

In nearly 10% of cases, this procedure results in a complete electrical conduction block.

The heart remains structurally intact, but electricity no longer circulates properly. At that time, this complication is often fatal.

The block is caused both by the suture itself and by swelling related to postoperative inflammation—a temporary situation, but one without an immediate solution.

A decisive intuition

Walt Lillehei then imagines a bold solution:

placing electrodes directly on the heart, tunneling the wires under the skin, and connecting them to an external power source.

The problem?

Such a device does not yet exist.

A decisive meeting

He then meets a young electrical engineer, Earl Bakken, and Bakken’s brother-in-law.

Together, they have founded a small company called Medtronic, originally dedicated to repairing electrical medical equipment.

Dr Lillehei explains exactly what he needs.

The transistor changes everything

This is the era of the arrival of the transistor, invented in 1947—an innovation that transforms electronics.

While browsing through magazines, Earl Bakken notices that the metronome, used in music to keep tempo, operates using a transistor.

A metronome can produce 60 beats per minute.

By adding a mercury battery, Bakken turns this idea into a device capable of delivering 60 electrical impulses per minute.

Immediate application to heart block

A few days later, Dr Lillehei once again faces a heart block during surgery.

He places two electrodes directly on the heart, brings the wires out through the skin, and connects them to the new device.

As soon as the device is turned on, the result is immediate:

the heart rate returns to 60 beats per minute.

A success… still imperfect

The heart beats normally again. A life is saved.

But the device remains outside the body, bulky and impractical for long-term use.

Once again, a major breakthrough has been achieved—

but it is clear that further progress is still needed.

Wilson Greatbatch: the pacemaker under the skin

In Buffalo, New York State, Dr Wilson Greatbatch, in collaboration with engineer Andrew Gage, develops a pacemaker that can be implanted under the skin.

This breakthrough marks a major turning point: the stimulator is no longer external, bulky, or connected to an outside power source. It becomes portable, discreet, and suitable for long-term use.

Åke Senning: the first human implantation

They were not, however, the very first to implant an internal pacemaker.

In 1958, in Sweden, Arne Larsson, a 40-year-old engineer suffering from severe heart block, receives the first implantable pacemaker in the world.

The device is designed by engineer Rune Elmqvist.

At the time, the pacemaker casing is the size of a hockey puck, far from the small devices used today.

This implantation— a world first — is performed by surgeon Åke Senning.

A life extended by technology

Arne Larsson dies in 2002, not from a heart condition, but from melanoma.

Over the course of his life, he wears 22 pacemaker units and uses five different electrode systems, a striking illustration of the rapid evolution of this technology.

The pacemaker designed by Rune Elmqvist is later acquired by St. Jude Medical, which becomes Abbott in January 2017.

After ending his career as a surgeon, Dr Walt Lillehei serves as medical director of the company, thus completing the circle between surgery and technological innovation.

Du pacemaker d’hier aux technologies d’aujourd’hui… et de demain

In the United States, more than 100,000 pacemakers are implanted each year, and nearly 500,000 people currently live with a cardiac pacemaker.

From bulky experimental devices to small, reliable systems implanted under the skin, the pacemaker has become an essential tool, saving and improving the lives of millions of people worldwide.

In less than a century, it has evolved from a large device placed outside the body to a miniaturized system implanted under the skin, capable of functioning for many years.

A new milestone has recently been reached with the arrival of leadless pacemakers.

Much smaller, these devices are implanted directly inside the heart, without a generator under the skin or wires connecting the device to the heart muscle. This approach helps reduce certain complications and expands treatment options for carefully selected patients.

And the future?

Progress continues at a rapid pace. Researchers are working on:

- even smaller and longer-lasting devices,

- systems capable of communicating with one another,

- pacemakers that automatically adapt to a patient’s needs,

- and, possibly one day, energy sources inspired by the heart’s own movement.

What remains unchanged, however, is the fundamental goal:

to maintain a reliable, safe heart rhythm adapted to daily life.

From the intuition of a few pioneers to cutting-edge technologies, the pacemaker perfectly illustrates how medicine moves forward — one heartbeat at a time.