Episode 11 – An Electrifying Breakthrough

- Home

- »

- History of cardiology

- »

- Episode 11 – An Electrifying Breakthrough

Congenital heart defects have long driven surgeons to develop new cardiac surgery techniques.

These operations, still experimental at the time, revealed three major types of complications:

- ventricular fibrillation,

- electrical conduction block,

- and the discovery, sometimes too late, of an inaccurate preoperative diagnosis.

Ventricular fibrillation: the most feared

Ventricular fibrillation is a fatal arrhythmia. The ventricles tremble chaotically, like Jell-O, without contracting effectively.

BloodBlood is composed of red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, and plasma. Red blood cells are responsible for transporting oxygen and carbon dioxide. White blood cells make up our immune defense system. Platelets contribute to blood circulation stops abruptly, and within seconds, life fades away.

In the 1940s, this rhythm disorder meant only one thing: death.

Dr. Claude Beck – The first electrical miracle (1947)

In 1947, Dr. Claude Beck, a thoracic surgeon in Cleveland, operated on a 14-year-old boy with a pectus excavatum, a malformation that pushes the breastbone inward and compresses the heart.

The procedure went smoothly until, suddenly, the boy’s pulseThe pulse is the sensation of beating that one feels by applying slight pressure on an artery, usually at the wrist or neck. It corresponds to the blood flow pulsated by the heart through the arteries with disappeared.

The monitor displayed a deadly rhythm: ventricular fibrillation.

At that time, there was no way to bring a fibrillating heart back to life.

But Dr. Beck refused to give up. He took the heart in his hands and began a manual cardiac massage at a steady rate of 60 compressions per minute.

He recalled earlier research from Geneva, around 1900, showing that an electric shock could restore normal rhythm in dogs.

He also knew of experiments by his colleague Dr. Carl Wiggers, who had designed a device capable of delivering an electric shock directly to an exposed heart.

Beck ordered that the device be brought to the operating room.

After 45 long minutes, it finally arrived.

Without worrying about sterility, he placed the paddles directly on the heart and delivered several shocks, combined with direct injections of medication.

Miraculously, the heart resumed its normal rhythm.

That day, Dr. Claude Beck had brought a human heart back to life.

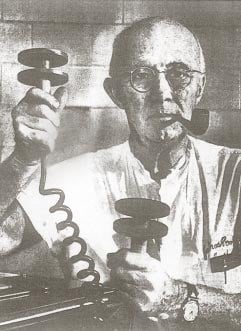

Dr. William Bennett Kouwenhoven – The shock through the chest

This technique, however, required an open chest. Could it be done another way?

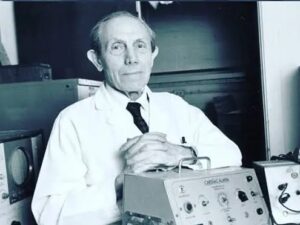

Dr. William Bennett Kouwenhoven, an electrical engineer and physician, devoted his work to the study of bioelectricity.

Between 1938 and 1954, he developed the first external defibrillator, capable of sending a life-saving shock through the chest without surgery.

While studying animals, he noticed that an electric discharge caused a palpable pulseThe pulse is the sensation of beating that one feels by applying slight pressure on an artery, usually at the wrist or neck. It corresponds to the blood flow pulsated by the heart through the arteries with in a dog’s leg.

This led to a revolutionary idea: chest compressions.

Kouwenhoven publicized this discovery, laying the foundation for modern cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

In 1957, his assistant Dr. Friesinger used the prototype for the first time on a patient who collapsed during a routine exam.

Following Kouwenhoven’s instructions, a young trainee performed chest compressions while the defibrillator was prepared.

At the second shock, the patient regained consciousness.

The first conventional resuscitation had just occurred.

These results proved that a combination of sternal compressions and artificial respiration could sustain life until effective defibrillation—making cardiac resuscitation possible outside the operating room.

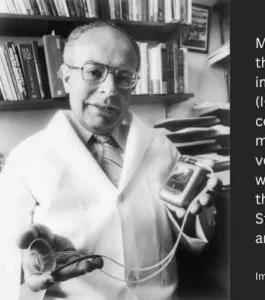

Dr. Michel Mirowski – The implantable defibrillator

Moving from an open-chest shock to one applied through the skin was a giant leap forward.

Yet for patients at high risk of sudden cardiac arrest, time was still the enemy.

Dr. Michel Mirowski envisioned a device capable of continuously monitoring the heartbeat and automatically delivering a shock when detecting a lethal arrhythmia.

The first prototype appeared in 1970, and after ten years of refinement, the first implantable defibrillator was successfully placed in a 57-year-old woman at risk of sudden cardiac death.

A new era had begun.

Dr. Paul Zoll – The portable revolution

Meanwhile, Dr. Paul Zoll, a pioneer in external pacemakers, focused on developing portable defibrillators.

In 1980, he founded Zoll Medical, which would become a world leader in external and automated defibrillators (AEDs).

Thanks to these user-friendly devices, thousands of lives are now saved every year by bystanders before emergency services arrive.

Conclusion

From Beck’s open-chest surgery to Zoll’s portable devices, the story of defibrillation is one of relentless determination against sudden death.

In less than half a century, science transformed despair into hope — an electrifying breakthrough that continues to save lives around the world.